Deconstructing Livingstone: Challenging the Colonial Legacy

The David Livingstone Memorial statue

The David Livingstone Memorial statue now stands in the square in front of Glasgow Cathedral. In 1875, two years after his death, a competition was held by the Glasgow City Council to erect a statue of the famed Scottish explorer, missionary and abolitionist. Glasgow-based sculptor John Mossman’s statue was selected and erected in George Square directly opposite the Merchant’s House in March, 1879. The unveiling was a grand affair attended by the Lord Provost and the daughters of Livingstone. During the unveiling speech, committee chairman James White of Overtoun recounted Livingstone’s disgust at the institution of slavery in Africa and ‘man’s inhumanity to man’. White was followed by the Lord Provost who stated;

“It would have indeed seemed strange if Glasgow, which owes so much of her progress and prosperity to the skill and energy of her industrial population, had failed to erect her tribute of respect, to the honoured memory of one who, as the humble mill-hand in the adjacent village of Blantyre, shared the experience of honest poverty struggling for a livelihood, and who raised himself by his own industry, thrift and indomitable perseverance to highest rank amongst those whose names shine most conspicuous in the history of African discovery. In this connection it is a noteworthy fact that nearly all the great explorers who have contributed to our knowledge of the extent, condition, resources and peoples of the vast continent of Africa have been Scotchmen…This, gentlemen, in a list of which Scotland has reason to be proud.”

The sheriff proclaimed Livingstone “one of Scotland’s representative men. If he was anything at all, emphatically he was a Scotchman. He rose from that great body of people, who made Scotland great.” The speeches, newspaper articles and poems paint Livingstone in a heroic light, but more importantly as heroically Scottish. Livingstone becomes a stand in of perceived Scottish ideals and characteristics; industrious, thrifty, Christian and a believer in abolitionism. Africa is depicted as a ‘benighted continent’ in need of saving, and as the late eighteenth and nineteenth-century maker of Scottish heroes. Here, Africa’s progress is presented as linked with Scottish determination. The fact that some of the earlier explorers were participants or passive observers of the slave trade is ignored. Furthermore, Scotland’s role in slavery and Africa is completely omitted and rewritten as the triumph of Scotsman.

Explorers such as Livingstone, Mungo Park and Campbell are the new Caledonians, the new heroes of Scottish myth; which is very apparent by the stories that surround Livingstone. It is not a coincidence that newspapers, even into the 20 th century refer to material culture left by Livingstone as relics. Although, the term relic can be used to mean artefact, it is often associated with the religion and objects of reverence. Only six years after his death; the tale of his attack by a lion, encounter with Stanley and his “30 attacks of fever” were cemented in the Livingstone mythology. Livingstone became the perfect figure in which to imbue the nineteenth- century Scottish national narrative, a Christian capitalist imperialist and in his statue he was seen as ‘Scotland’s representative man’.

David Livingstone

Courage takes many forms. It may be fleeting and spectacular or lasting and routine.It was the latter variety that Dr David Livingstone displayed during his life-long dedication to uncivilised Africa last century.

In opening up the dark interior of Africa he did more than form trade routes and evangelise the sceptical natives. The doctor worked tirelessly and successfully for the suppression of slavery.

-Dundee Courier, 13 August, 1954

David Livingston Centenary

The Scots as a nation have bred great explorers with a large prodigality. They have been chiefly responsible for the opening up of Africa – James Bruce did the Nile, Mungo Park the Niger, and David Livingston the Zambesi. Captain Cook, whose discoveries in the South Seas helped to add a Continent and two Dominions to the British Empire, was the son of a Scottish Borderer.

-Aberdeen Press and Journal, 07 December, 1940

Livingston rent the veil which for ages had shrouded the fair features of the Dark Continent… Throughout a territory of nearly one million square miles he pioneered mission, blazed a track for commerce and forced the strongholds of slavery…Africa completely imposed her seductive spell upon the heart of Livingston…But the magnetism of Africa does not explain the sacrifices of his life…Slavery, itself, he annihilated by opening a pathway into its secret haunts for the regenerative impulses of Christian civilisation…I realised but feebly the debt which African civilisation owes to that great man, and the permanent and solid value of his careful researches into the physical condition and natural history of the Dark Continent.

-Milngavie and Bearsden Herald, 14 March, 1913.

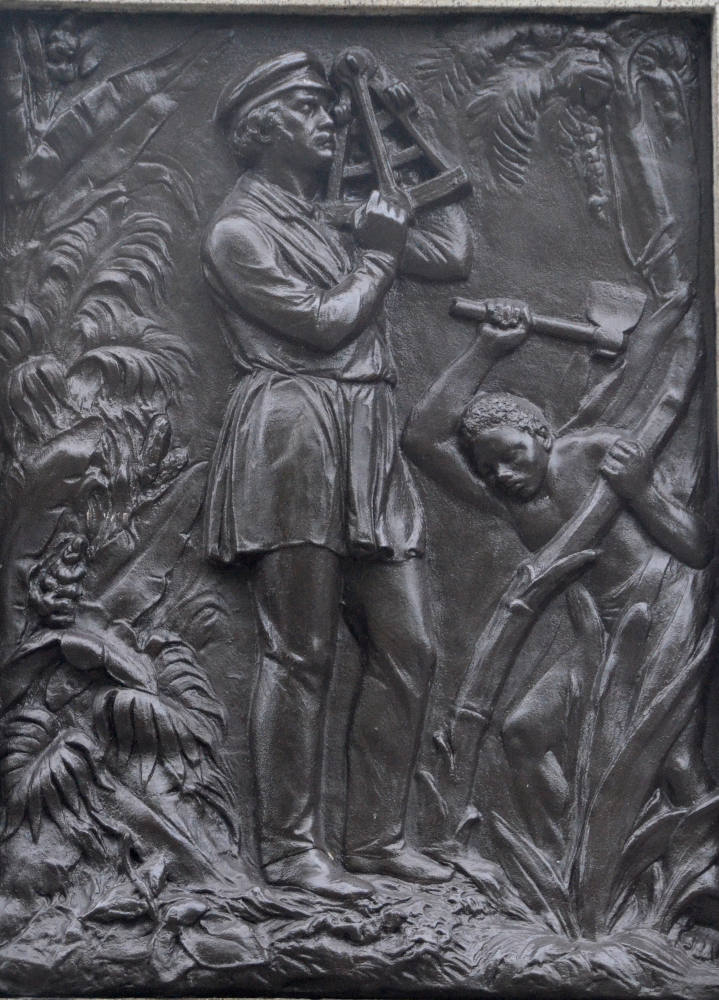

In 1959 the Livingstone statue was moved from George Square to Cathedral Square. The ideas and stereotypes that are illustrated in the writings on Livingstone are reiterated and visualised in the statue. It reveals the tension between the evolving national narrative and Scotland’s slave past. The main figure of Livingstone stands on a rectangular granite plinth with a bronze relief on each side. Three of the reliefs depict various scenes associated with Livingstone; an Arab slave trader holding a whip over a half-naked African woman.

Livingstone holding a sextant in the African jungle with a sparsely clothed African man clearing his path with a cutlass, and narrative scene showing an African family of a shackled man, distraught woman holding a baby looking up to Livingstone hopefully as he reads the Bible. The scene continues with the man freed from his chains and holding a spear, and the woman reading the Bible to her child, the two images of the family is centred by the serene bible-reading Livingstone figure. The reliefs depict Livingstone as the civilizing, intellectual hero of the African family. He is the quintessential ‘white saviour’ or Scottish saviour, however more than that he is always depicted in a position of power over the Africans. In the family scene, he is the focus of the image and the Africans are literally and metaphorically looking up to him. In the exploring scene, he is depicted with an instrument of progress and civilization, the sextant. Scientific equipment, in this instance surveying tools are not innocuous objects, but objects of Empire. Through surveying, mapping and naming, colonial agents exercise power and Western ideals over the landscape. It is through geographical works by Livingstone and other explorers that the ‘dark continent’ was mapped and thus able to be divided up by colonial powers at the Berlin Conference in 1884.

Livingstone holding the sextant in contrast with the African laboring to clear the path with a cutlass, immediately shifts the power dynamic between the two characters. The image is reminiscent of earlier prints of overseers watching slaves work in cane fields. Livingstone is not holding a whip, but the sextant here serves the same purpose as to create a power differential that would be readily understood by a British viewer, even more so when it is pointed out that cutlasses were often termed negro knives by Scottish merchants exporting the tool to West Indian slave plantations. Furthermore, the sextant is equated with scientific intellect and the cutlass is a laborer’s tool assigned to corporeal form, reinforcing ideas of race that began to arise in the previous century. Thus, the pre-abolition ideologies of white superiority still pervade the creation of Glaswegian identity.

The story of Livingstone and the ‘Scramble for Africa’ can be further explored with a closer look at the Berlin Conference and also reflects European sentiment towards Africa and Africans. Although the conference occurred ten years after Livingstone’s death his presence is felt. In 1884, the Berlin Conference marked the official beginning of colonialism in Africa. In his opening speech at the conference, Otto von Bismarck, Chancellor of the German Empire, quoted Livingstone, referencing his 3 C’s of Christianity, Commerce and Civilisation. Livingstone believed the 3 C’s would end slavery in Africa and ‘free’ black people. One of the justifying principles behind colonialism was the need to civilize the purportedly ‘backward’ peoples of Africa. This reasoning is illustrated in the articles of the Berlin Act of 1885;

Article 6

All the Powers exercising sovereign rights or influence in the aforesaid territories bind themselves to watch over the preservation of the native tribes, and to care for the improvement of the conditions of their moral and material well-being, and to help in suppressing slavery, and especially the slave trade. They shall, without distinction of creed or nation, protect and favour all religious, scientific or charitable institutions and undertakings created and organized for the above ends, or which aim at instructing the natives and bringing home to them the blessings of civilization. Christian missionaries, scientists and explorers, with their followers, property and collections, shall likewise be the objects of especial protection. Freedom of conscience and religious toleration are expressly guaranteed to the natives, no less than to subjects and to foreigners. The free and public exercise of all forms of divine worship, and the right to build edifices for religious purposes, and to organize religious missions belonging to all creeds, shall not be limited or fettered in any way whatsoever. Article 6 when mentioning religious freedom, refers only to Christian religious freedom, and empowers religions to set up missions and churches with the specific purpose of “bringing home the blessings of civilization” to the natives. The 3C’s justification permeated European involvement in Africa well into the 20 th century and was the founding tenants of the Glasgow-headquartered African Lakes Corporation, that controlled the area of modern-day Malawi for decades. The 3 C’s, although an abolitionist in explanation was in fact deeply rooted in racist ideas of superiority of white religion and culture and was wholly hegemonic in its approach.

The colonisation of the African territories was of course not presented as hegemonic march, but a moral imperative or as Rudyard Kipling immortalised in his 1899 poem, “The White Man’s Burden.”

Take up the White Man's burden —

Send forth the best ye breed —

Go bind your sons to exile

To serve your captives' need;

To wait in heavy harness,

On fluttered folk and wild —

Your new-caught, sullen peoples,

Half-devil and half-child.

Take up the White Man's burden —

In patience to abide,

To veil the threat of terror

And check the show of pride;

By open speech and simple,

An hundred times made plain

To seek another's profit,

And work another's gain…Take up the White Man's burden —

And reap his old reward:

The blame of those ye better,

The hate of those ye guard —

The cry of hosts ye humour

(Ah, slowly!) toward the light: —

"Why brought he us from bondage,

Our loved Egyptian night?"

BACK TO THE LIVINGSTONE STATUE!

In an attempt to reinforce the image of Scotland as abolitionist, the slaving relief, depicts the slaver as Arabic, referencing the ongoing East African slave trade controlled by Arabic groups. Of course when the statue was erected both the Portuguese and Spanish were still slave traders and owners, but the choice to depict the Arabic slave trade distances slave-ownership from the white European. The Arab slaver is an ‘other’ and therefore cannot be conflated with whiteness, serving to erect a divide between the slave trade and the Scottish consciousness, Slavery thus only becomes a familiar entity within the Scottish imagination in terms of abolition, reinforced by the image of white Livingstone reading the Bible to the once enslaved family. Although placed on opposite sides in order to enhance the contrast, the Arab slavery and the explorer reliefs are actually telling a similar story, suggesting that there was a deep disconnect between the imagined Scottish narrative and the reality. The space in between that disconnect is where the erasure of the Scotland’s slave history and slaves occurs, the more the abolitionist image was solidified the more the enslaved who built Scotland fade into history.