History of Logging in the British Atlantic

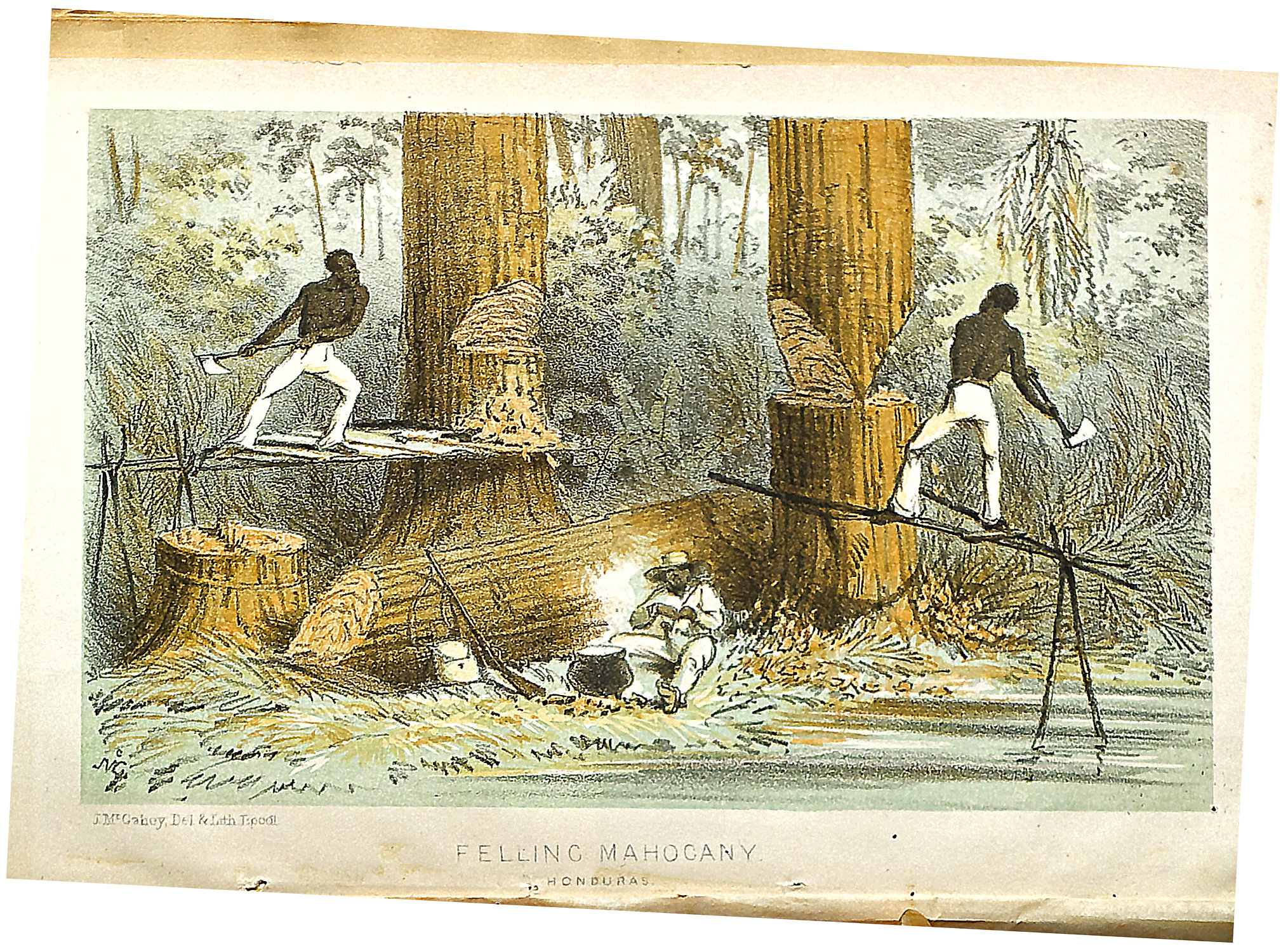

“Felling Mahogany in Honduras” depicts cutting the trees to make furniture for the wealthy, as slaves did across the Caribbean in the 18th century. Credit: New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, New York.

Unlike in the West Indies, where mahogany logging was a precursor to clearing land for plantations, woodcutting, especially of mahogany, was the primary economic venture in the Bay of Honduras. Furthermore, British logging merchants or ‘Baymen’ could not officially own land in Spanish territory, thus owning expert gangs of slaves was their most valuable commodity and influenced their access to mahogany and overall success.

Mahogany typically grew dispersed across vast stretches of rainforest, and thus requires small groups of slaves to range widely remote areas with minimal supervision. Slaves played a vital role in locating and felling trees. Locating the elusive mahogany trees required expertise, and was entrusted to a skilled slave designated as the huntsman and who lead each logging gang. The huntsman’s job was to find the trees, often by climbing tall trees and surveying the forest canopy for the desired mahogany and then leading the team to the trees’ location. Once, located, a high platform was constructed on either side of the trees and the axemen, balanced on the platforms set about felling the massive trees. The felled trunks were then stripped of branches and the edges squared. The logging gang then spent weeks clearing a miles long path through the rainforest and transporting the logs to the nearest river. The logs were then floated down the river during the torrential rains of June/ July and corralled at the Bay to be loaded into ships using winches to hoist the trees into the hold of the ships. The entire process of felling mahogany proved to be extremely dangerous, the forest presented a number of dangers from poisonous animals, disease, dehydration and bay sores that caused lesions. Furthermore, loading the logs at the Bay had to be done while avoiding coral reefs and sharks.

The remote nature of mahogany logging offered a more flexible form of bondage and also greater opportunities to run away. The Baymen thus controlled their slaves using a series of incentives, harsh punishments and promoting unsavoury stories of their Spanish neighbours as a deterrent. However, the secluded nature of logging and dependence on the knowledgeable slave tree-fellers created a unique dynamic between slave masters and slaves in the Bay settlement. The early settlement also had a lack of white female settlers, which resulted in a significant mixed-race population as the white settlers turned to enslaved African women and free women of colour as sexual partners.

In the years following the British abolition of slavery in 1834, ex-slaves and the growing Creole and mixed-race population continued to work in the timber industry. The rigid class and racial hierarchy hindered them from pursuing new avenues and the generational knowledge of logging made them valuable assets in the logging industry. However, although assets these labourers were rarely sufficiently compensated and former slave owners actively restricted their economic freedom by denying them access to land and maintaining a credit system.

In 1862 the Honduras Bay settlement was officially declared a British colony. With the formation of an official colony came an influx of more British persons, predominantly representatives of London merchant houses and approximately 400 Scottish tradesmen. A Scottish element had been present in the area prior to 1862 and economic hardship and urban industrialization in Britain had fuelled Scottish emigration in second half of the 19th century. Colonial Secretary Henry Fowler stated; “The Europeans or Whites (principally Scots) are birds of passage, business or duty calling them there, but very few entertain the thought of making permanent homes in the Colony.” Fowler’s statement suggests that like many of their West Indian counterparts Scottish-Honduran merchants were sojourners, transitory fortune seekers. In the late 19th century, the Creole elite, White settlers and Scottish merchants formed a powerful unit that exerted considerable influence on the colony’s administrative, political and economic structures. An 1895 article in the Times of Central America complained that, “So long as this clique continues to govern the Colony, so long it will remain the same miserable neglected place.” The control of the white elite extended into the ownership of the majority of forestry land, and they maintained a state of semi-slavery among the Creole loggers, who were kept dependant on the white-led corporations such as the Belize Estate and Produce Company for a livelihood. This system persisted until labour protests broke out in 1934, eventually leading the British government to legalize unions, institute minimum wage, and eradicate the credit system used in the timber industry.

In 1942, 900 Belizean lumberjacks were recruited by the British government to fell trees in Scotland as part of the Ministry of Supply’s World War II war effort. The lumberjacks became known as the British Honduras Forestry Unit. These men were part of the Belizean logging history, which for almost 200 years had used slavery and then slave descendants as a labour force in a profitable industry.