Slavery memorials are coming down

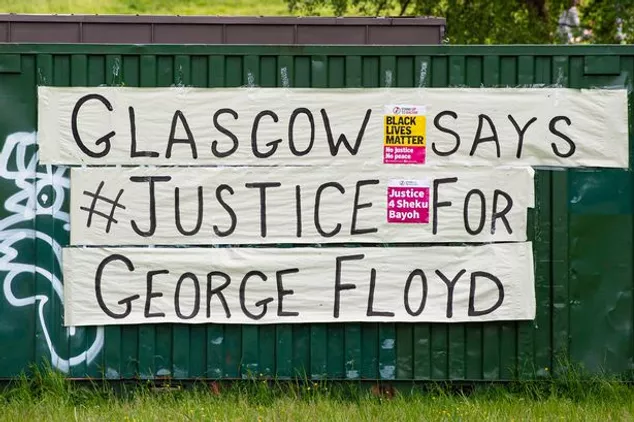

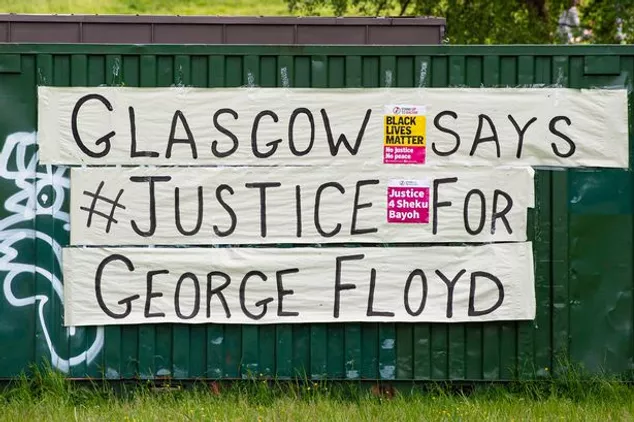

Now, some three years later we once again find ourselves debating what to do with public memorials to the trans-Atlantic slave trade only this time with the killing of George Floyd and the international protests that have followed forming a powerful backdrop and impetus. This impetus has led to direct action such as the tearing down of the statue of infamous slaver Edward Colson in Bristol and the installation of alternative street names across Glasgow’s Merchant City by Celtic’s North Curve fan group juxtaposing names of streets named after slavers with African American figures including Harriett Tubman, Rosa Parks and George Floyd.

These are highly symbolic, important moments and they should be applauded, but they should also be recognised for what they are, limited actions which address some visible symptoms of an illness but do not treat the deep-rooted malaise of the selective and half-truths that Britain uses to form the molecular bonds that bind the national project together.

History has always been the place from where we imagine ourselves, the place we look back to before thinking about how we will go forward; how we face the future without losing the quintessential values that make us who we are, those things that make us great. The problem, of course, is that looking back seeking certainty makes one an unreliable narrator. As we go to the well of the past seeking only to draw on those things that affirm who we are, we ignore that which contradicts.

We have seen this before the last time there was mass public debate about the Atlantic Slave Trade was in 2007 a year that saw a plethora of exhibitions, art commissions and other public programming exploring abolition of the slave trade. Evaluation of those events found that white Britons preference to remember only through abolition, thus overcoming and obscuring the painful recognition of complicity in the Atlantic slave trade itself. Remembering the work of the abolitionists, focusing on their moral fortitude and perseverance provided white audiences with a more comfortable place from which to construct a sense of identity and self.

Today we see it when Prime Minister Boris Johnson weighs into the debate arguing that the removal of statues amounts to rewriting British history and launching a staunch defence of Winston Churchill lauding him as “one of the country’s greatest ever leaders” and declaring it the “height of lunacy” to accuse Churchill of racism. From this position, it is not possible for there to be a great leader and champion of British values and simultaneously be a racist: the two things are supposedly mutually exclusive, but this is a position that history does not support.

Churchill is accurately described as a great wartime prime minister and a racist. He undoubtedly played a great role in defeating Nazi Germany but he considered colonial subjects as "helots", or slaves, whose only reason for existence was the service of racial superiors and of whom Leo Amery, Secretary of State for India and Burma wrote in his diaries that he did not "see much difference between [Churchill's] outlook and Hitler's”. This historical dissonance has long gone unreconciled but history is not without a great sense of irony, and the very facts of history that have been largely ignored, slavery and empire, are the very ones that have led to this moment. It is easy to sustain an image of yourself based on half-truths if the other half is always hidden. Britain’s transformation into a multicultural society brings together several communities whose relationship to the same historical events and figures are often in conflict with each other. White Britain may like to imagine Victorian England as a time of respect for law and order, responsibility, and tolerance but for Black Britons, Victorian Britain was a time of race-based oppression, forced migration and systematic dehumanising. White Britain can safely imagine Churchill as a great defender of democracy but for South Asian Britons he is democracy’s great adversary. This tension is not gentle and calls into question the very idea of Britishness, but it is also a tension that can no longer be easily resolved by ignoring the bits of the past that make us uncomfortable.

Black Lives Matter challenges us to seek out and eradicate systemic race-based inequality to do that effectively we must now, finally, begin the task of understanding how that inequality came to be systemic. Understand how British public history, in particular, has variously glossed over Empire and the slave trade and created safe distance from it by erroneously constructing it as the history of others. Recognise that this has left Britain at a disadvantage when understanding both its place in a globalised world and why 21st century Britain looks the way that it does.

Boris Johnson may be concerned about the rewriting of British History, but this is precisely the task that is now required especially for those involved in public history, to write a complete more accurate history. This is not as Mr Johnson suggests a bad thing, it is necessary if we want to have meaningful change. But we must also recognise that this goes beyond the removal of statues and has to include building an understanding of how the horror of the past still profoundly affects us all: from the structural effects such as overrepresentation of Black people in the criminal justice system to the banal, like the tradition of Afternoon Tea. The task before us now is to find ways to take a real look at who we were so we can understand who we are and how to build the society we want to be. This means transforming our relationship with the past and we must not settle simply for the redecoration of public spaces by removing public memorials.