The British Atlantic, Scotland and Mixed Race

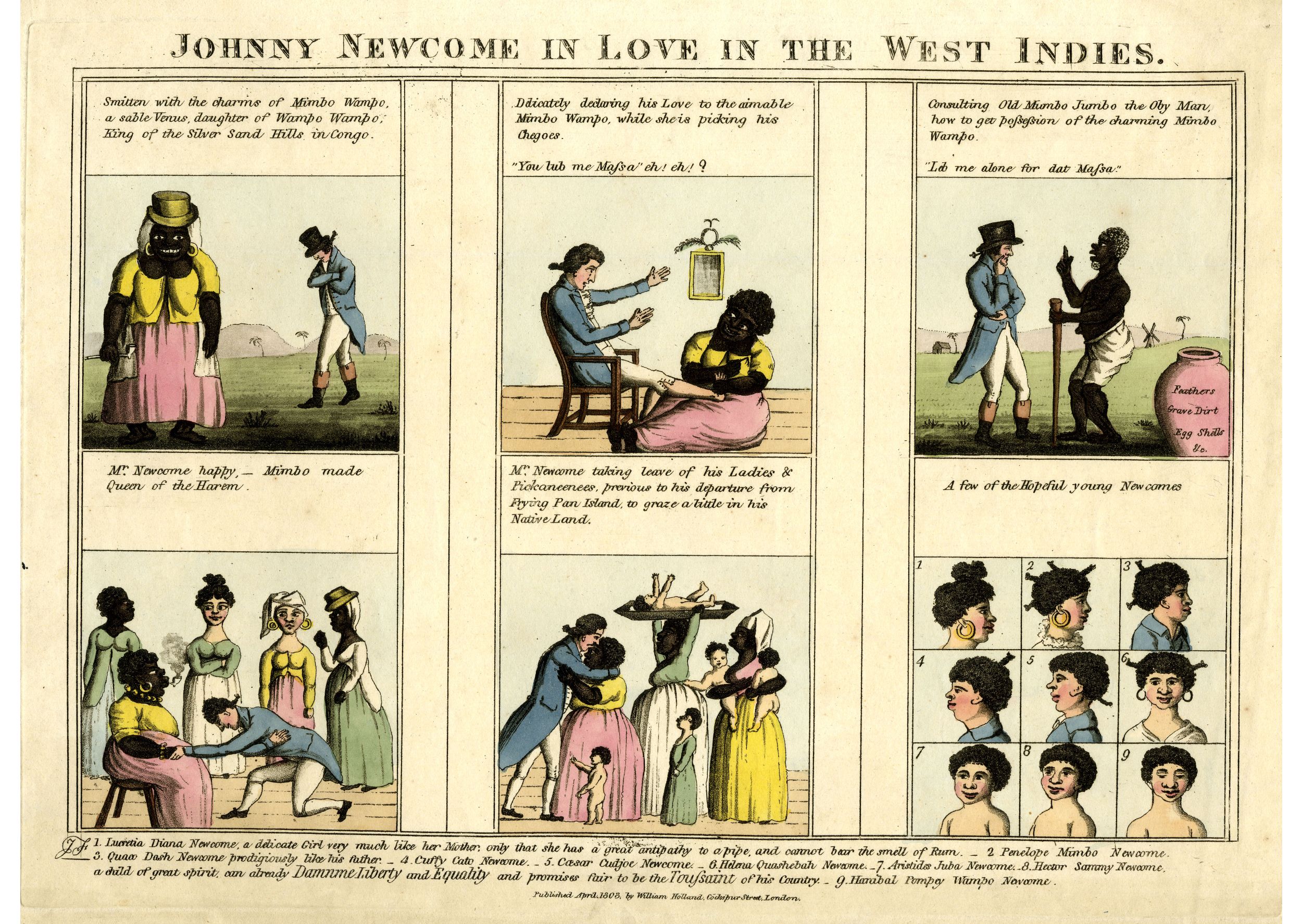

Published by William Holland, Cockspur Street, London, Johnny Newcome in love in the West Indies. April 1808, © The Trustees of the British Museum

Race in the British Atlantic World

Scholars still debate how the complicated and constructed idea of “race” developed in the modern world. British beliefs about a difference between Africans and Europeans pre-dated imperialism. Early theories focused on multifaceted distinctions – such as religious, cultural, linguistic, and complexional characteristics – among the two locations. Status was also a key marker. There is some evidence that British planters in the Americas did not initially differentiate strongly between white indentured servants, African bound laborers, and indigenous workers. In the 1660s, though, as British servitude decreased and the transatlantic slave trade ramped up, colonial officials throughout the Americas started crafting laws specifically targeted against non-white peoples to create a race-based plantation system.

Over the course of the eighteenth century, pseudo-scientific speculation and pro-slavery defenses further simplified these broad ideas into a narrow prejudice against skin color. Attributing mental acuity, physical stamina, sexual appetite, and other factors to coloration allowed imperial regimes across the Atlantic to justify the enslavement of millions of Africans, Amerindians, and their descendants. It also supported a system of white supremacy in which the law, economy, and culture of colonial society discriminated against people of color, both free and enslaved. There was not, however, a uniform implementation of racism in the British Atlantic. Each colony maintained its own laws and traditions, shaped primarily by its demographic structure: majority-black colonies often had the harshest, though sometimes most complicated, attitudes and punishments. Because of the constant circulation of people and ideas in the British Empire, these notions were not confined to the Americas. Although English and Scottish law contained almost no statutes on slavery or issues of race, non-white residents and migrants to Britain frequently suffered intense discrimination as well, up to the present day.

Mixed Race in the British Atlantic

From the very beginning of colonization in the Americas, British men had sex with non-British women. In most of these cases, British adventurers preyed on indigenous and African victims. Sexual violence was one of many tools of exploitation. It sent an intended message about power and control to those societies over whom the British wished to dominate. These interactions, of course, frequently produced children. With virtually no traditions marginalizing individuals based on coloration, most Amerindian and African-descended peoples in the Americas had little reservation in accepting these children into their communities. To white colonists organizing race-based laws and social structures, however, mixed-race offspring presented a major challenge to emerging European theories about racial difference.

By and large, colonists in British America lumped mixed-race people into the marginalized categories of their non-white parents. Colonial law frequently put “mulattos” into the same legal status as “Negros” and “Indians.” This is often referred to as the “one-drop rule” of racial descent: a polarized system that some have argued was distinct in the British Atlantic. Some scholars have claimed that British culture – due to Protestant individualism, demographic isolationism, and other factors – was less tolerant of mixed-race people, compared to the Spanish, Portuguese, and French empires. But colonial attitudes, and laws, varied across the British Atlantic. Moreover, there are many cases in which white parents treated their interracial households as true families.

Some lived openly with non-white partners, and others sent mixed-race offspring to live with British family to escape colonial persecution.

Historic Scotland & Mixed-race Children

In some extraordinary, but not altogether rare, cases, Scottish fathers sent mixed-race offspring to Britain. The reasons were numerous. Children could receive better educations there, could train for stable professions, could find marriage partners, or could simply escape colonial prejudice. John Tailyour, a Jamaican slave merchant originally from Angus, sent at least three mixed-race children to stay with his Scottish family at the end of the eighteenth century. The children lived for a short period with their aunt in Montrose, before attending school in Yorkshire. The eldest son went on to join the East India Company Army, and later shipped off to Chennai. In their correspondence, the Tailyours did write openly about their West Indian relatives’ African background, but appear to have taken good care of the children. However, other mixed-race Jamaicans at this time – notably Robert Wedderburn and William Davidson – remarked upon the pronounced racism that they experienced in Scotland when they arrived.